Slow phase separation, multiple experiments

The critical importance of operational flexibility

One of the most important capabilities that we get as scientists working with NASA with experiments onboard ISS is a great deal of flexibility. This may manifest in several ways, most obviously the fact that ISS is a manned platform, so that we have astronaut crew members as our project scientists; our fantastic crew members have collected data and made critical suggestions for improvements to our previous BCAT experiments, allowing us unprecedented flexibility in experimental development as the experiments are run.

But the flexibility may be manifest in other ways, as well. Although we are constantly harassing the long-suffering schedulers to make changes—an OCR (“operations change request”) coming from us may have only 3 letters, but is possibly seen as a four-letter word in some places!—they have real scientific benefits. What we have been able to distinguish in the results of the fourth run of ACE-M2 is a significant distinction between slow phase separation and gelation is only possible because we kept changing the plan and extending our run. It is not possible to determine how long these samples will take to evolve, or even if they will evolve at all in the absence of significant gravity—which is why it is so important to run these experiments onboard ISS. If the ground-based results could be used to predict deterministically what happens on orbit, then there is not a huge benefit to going to all the trouble and expense of running on orbit. Therefore, when we are asked to give some estimates as to how long it takes to run, or how many images we want, etc. etc. we are obliged to give a best guess, but clearly this cannot represent a true prediction, because learning something new is the whole point of doing science! So a big thank-you to them for bearing with all of our changes, because those changes and constant flexibility are critical factors in our being able to learn new things and have scientific results to share.

Another major benefit of the current paradigm of on-orbit operations is the ability to conduct independent investigations on the same samples, using completely different experimental techniques and apparatus to probe the same samples. Once the materials are all certified by the safety folks as good to fly, we can then do a lot of things to get at potentially the same science from different angles, substantially increasing the robustness and generality of our results.

BCAT-KP and ACE-M2: the same colloid-polymer sample

As a result of these factors, we have been able to launch and observe the behavior of a phase-separating colloid-polymer mixture, sample number 20, (platter 2104, strip A-612, well A5):

We launched the same sample 20 in another well (platter 2104, strip C-621, well C5), but that well has a slowly growing bubble, and thus the sample data is not valid, which will be discussed elsewhere.

The original experiment: 2.5-week run

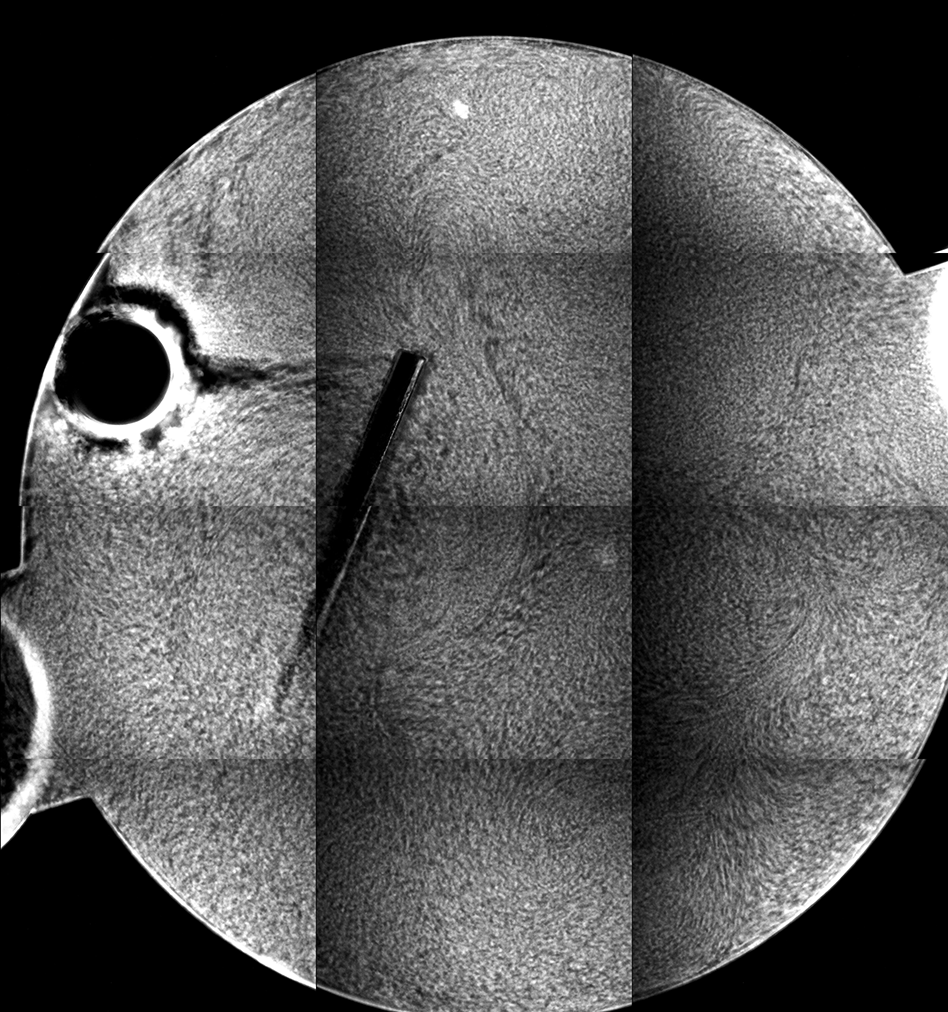

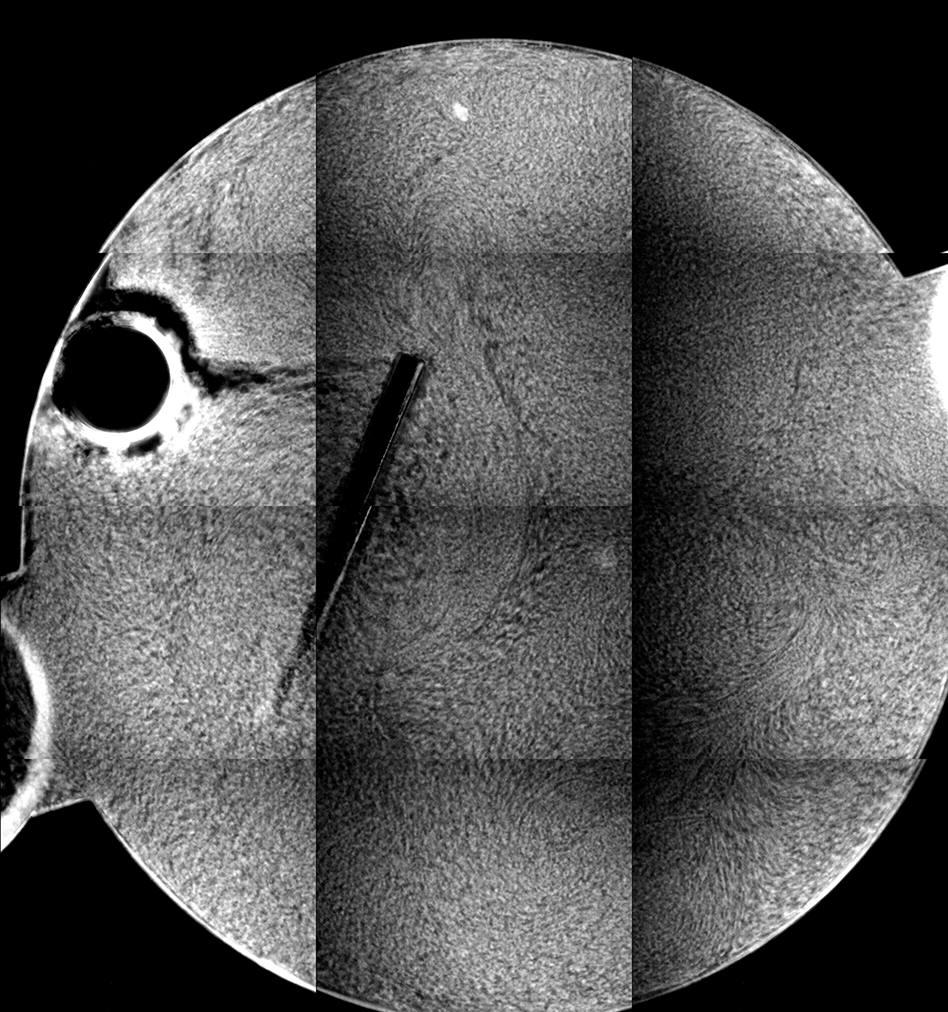

We originally planned to image the phase-separating and gelation samples over thee course of a period of two and a half weeks; this timescale was set by the BCAT series of experiments, where we see significant, often complete, phase separation in just a couple of weeks. After two weeks (day 15 of the experiment), the sample had undergone some phase separation:

We reran the same well three days later (day 18 of the experiment), and the image is nearly identical:

The differences were almost imperceptible, and so I had concluded at the time that not much was happening in the sample, and we should move on.

Flexible operations: returning to the same sample months later

In the past week or so, we have been able to finish our run with the other platter 2105, and switch back to platter 2104 for another look.

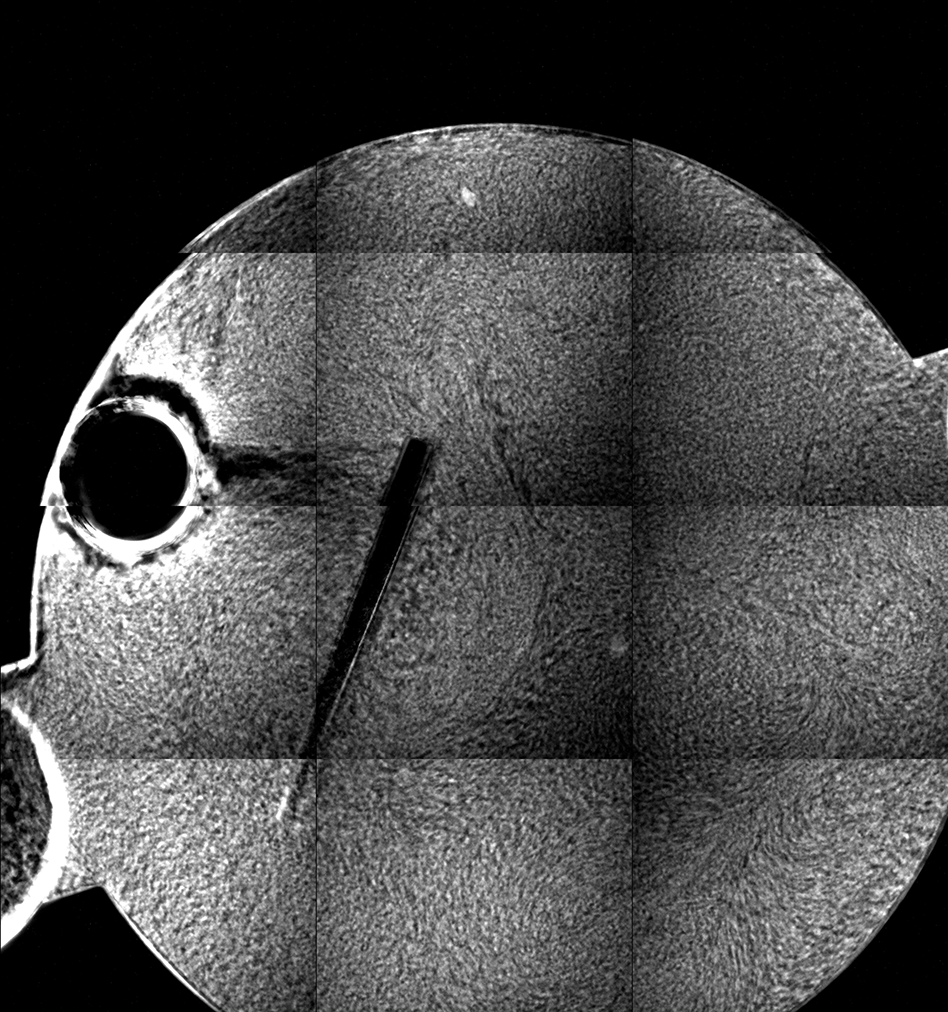

As a result of the flexibility in operations, and planning, we were able to collect this composite image at 10x magnification, on day 74(!) of the experiment:

There is a bit of shift, and the image is a little darker due to the problems we are having with the lamp, but this image is quite interesting for several reasons:

-

The overall structure of the sample is the same, the bubble and stir bar are in the same position, and the light and dark regions are basically in the same place. So the structure we saw hasn’t really moved around or rearranged.

-

However, the thickness of the “arms” of the structure is a bit greater; that is, the structures have coarsened. They have slowly evolved in time.

Thus, we have been able to run for basically eleven weeks (so far), and only see phase separation developing on those time scales. Checking images from a couple of days apart doesn’t show this evolution.

BCAT-KP sees something totally different

When we run the same sample in BCAT-KP, with the much larger sample chamber and using photography, we see complete phase separation. A network forms, it coarsens, and eventually all of the colloid-rich regions end up coalescing onto one side of the sample chamber. By contrast, the evolution here in ACE-M2, with a much smaller sample chamber, is orders or magnitude slower.

This is a particularly interesting scientific result, because it says that the rate of phase separation is strongly dependent on the container, at least up until a certain limit.

-

The ACE-M2 sample chambers are a couple of hundred microns thick, at its thinnest point.

-

The BCAT-KP sample chambers are several millimeters thick (>10x thicker), at its thinnest point.

-

However, the actual particles and polymers in the samples are a few hundred nanometers thick. The ACE sample chamber is, therefore, about 1000 particle radii thick, and the BCAT-KP sample chamber is about 10,000 particle radii thick. One would expect that this is large enough that the samples would not have significantly different phase separation behavior, because the particles in the middle are hundreds of particle diameters from the walls.

Yet this is not the case, and we see order of magnitude disparities in the rates of phase separation.

Science that can only be done on Space Station

This experiment, which effectively has run for multiple months in several different ways, has led to results that could only be done on ISS, for several reasons:

-

We need to have a stable platform that is continuously on orbit for several months. As of right now, no short-term vehicle (e.g. the Space Shuttle, SpaceX) can match that long-time capability.

-

We have needed to change the experiment and its parameters, in response to the data we are receiving. This interactive modality thus requires a manned orbital platform; it might in principle be possible to run this on an unmanned vehicle, but realistically, we would probably need several flights to iron out the kinks and would likely have a few total failures before getting it right. As will be described, we have suffered a broken sample, growing bubbles due to improper sealing, lamp intensity fluctuations, and a few other things; these can be mitigated when we have people around who can run tests, troubleshoot equipment and replace parts. It’s not possible if it’s floating in space with no one to access things.

-

We need flexibility in operations, thanks to the planners / schedulers / flight-ops folks. There are lots of activities going on, and we are grateful for the opportunity that NASA has given us to substantially increase and extend our experiments. Without these extensions, and with only a short run of data, we would never have been able to see the things we have seen.

I know our team, and myself specifically, are not always the easiest to deal with, but that is because doing science is hard, and on-orbit is even harder, and if we don’t push, we wouldn’t actually get all the way to the end to some interesting results. But hopefully I have presented to the reader why the ISS is necessary for the kind of science we are doing, and uniquely suited in its capabilities to doing the science that we seek to do. There simply is no alternative facility that provides nearly the same capabilities, and a critical part of those capabilities are the people who operate, control and plan activities for our experiment in particular and the ISS in general, from NASA, its contractors like our team at ZIN, and many others whose efforts we will never be able to know in detail. Yet this combined effort is the only reason we have the results we have.

Why does this matter? Practical applications

Finally, I believe these results may raise questions that are important to practical applications. Going back to the issues of product stability, basically no one talks about the containers, or even the geometry of confinement than may influence processing and storage. Our research is at a more fundamental level than the important work by companies to take our findings and bring them to the market. But the data we have collected requires an explanation, for how such changes in container size can have such a dramatic impact on phase separation rate.

What this does show is that our model colloid systems, as clean as possible and, on ISS, free of as many other forces (such as sedimentation) as we believe is possible, have very interesting behavior that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Industrial systems add more complication, and thus must consider the physics that we are finding affect our systems, as one of the many important factors in product decide. Clearly, though, these factors are irreducible, insofar as confinement and container issues simply cannot be ignored, and are responsible for interesting and unexpected behaviors that give additional parameters to industry for product design and optimization.